Fall Fire Farm is home to some of the oldest known breeds of turkeys

Fall Fire Farm is home to some of the oldest known breeds of turkeys

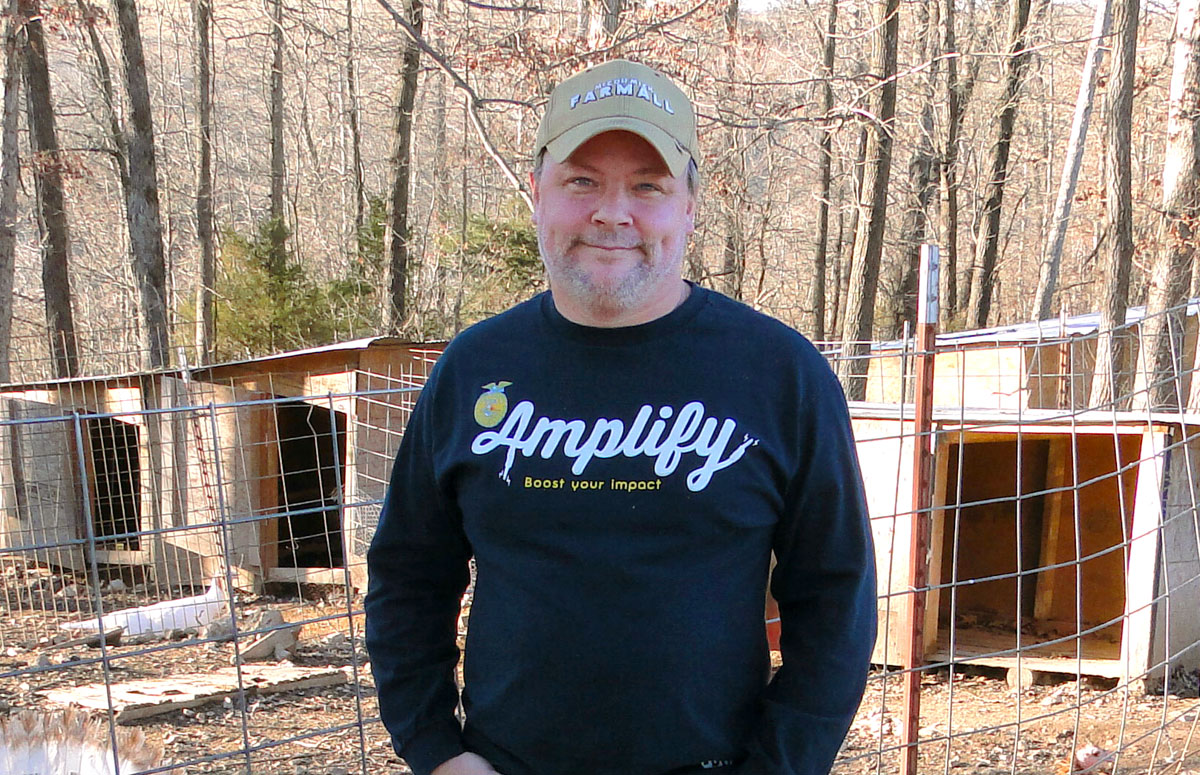

Getting out of the car at Zane Graham’s Fall Fire Farm in Hindsville, Ark., is a joyous but shocking experience; a swarm of large, distinctively colored heritage breed free range tom turkeys.

“Turkeys are creatures of habit and rather like dogs as long as you handle them when they are young,” Zane explained. “They have no fear and love to be around you.”

Zane was born in Madison County, Ark., and remembers his grandparents, Clifford and Rema Ahart, and his first view of a Bourbon Red turkey. His grandparents raised heritage turkeys as a hobby with Clifford working as a carpenter and for Ralston Purina. Zane never lost his fascination and solidified his preference for heritage breeds by working in a production turkey operation during high school and college. Zane graduated with a teaching degree and has taught third grade in the Siloam Springs (Ark.) School District for 13 years. For the first five years Zane lived in Bella Vista, but turkeys never left his mind. During those years, he searched the Internet to learn everything he could in addition to wanting to return home and raise turkeys like his grandparents. Six years ago he purchased 5 acres in Hindsville, where he now manages 250 to 350 breeders of 35 different varieties on an acre and half of that land.

“I guess the love of turkeys skipped a generation with me, though my 12-year-old son Colton helps with chores and has his own birds in order to make spending money,” Zane said.

Zane’s heritage breeding operation is rare. While in the learning stage, he found rare turkey breeder Kevin Porter’s site the best source for information and birds. Though the two have never met, they have had many phone calls and exchanged many emails.

The Fire Farm operation is comprised of several different components. Each breed is separate from all the others with pens from 10-feet-by-10-feet to 20-feet-by-10-feet, depending upon the number of birds in that particular varieties’ group. Any bird not true to the variety is culled. Each pen contains shelter, some with doors and others only a roof. Other parts of the operation include a Georgia Quail Farm cabinet incubator, which holds 210 eggs, and a GQF hatchery, both of which are located in the house.

The hardier and more disease resistant heritage turkeys don’t require the same living conditions as production turkeys. Production turkeys are broad breasted, and grow too big for their bodies. They also cannot reproduce naturally. Heritage turkeys have more dark meat, a more distinctive flavor and reproduce naturally with minimal health issues.

All turkeys have parasite issues and Zane must be his own veterinarian since heritage turkeys are so rare. Through careful study on the Internet, he has learned to use products made for other species such as pigs, horses and cows.

“You can get a turkey cold, you can get a turkey wet but you can’t get a turkey both cold and soaked without problems,” Zane explained. “These turkeys are similar to wild turkeys with the same kind of heartiness and disease resistance.”

The farm sells eggs and poults, both of which are ordered before the spring selling season. Eggs are his largest commodity because they are shipped nationally, even as far away as Hawaii and New York, while poults must be picked up at the farm. As soon as an egg is laid, the variety is written in pencil on the shell and then moved into the house where the eggs are sorted into those that will be sold as eggs and those that will hatch. Those sold as eggs are placed in cartons inside the warm house and turned daily until they are shipped, which is done once a week. Those that will hatch are first placed in the incubator, where they remain for 25 days, then moved to the hatcher. They are kept off the ground until 6-weeks-old, at which point they become part of the breeding flock. A few extra toms are sold in the fall.

Selling internationally is highly complicated because of mountains of paperwork relating to disease issues as well as being cost prohibitive, something Kevin Porter discovered when he ordered 40 eggs at $100 each in order to obtain a rare spotted gene. The spotted turkey died out in America but popped up in Australia. Only eight of the 40 eggs hatched and the gene was subsequently found to be different than the native American spotted breed called Nebraska. That breed appears to be gone.

Unlike any other areas of production agriculture, the genetic base for heritage turkeys is extremely small with breeds disappearing. One of the oddities is that the heritage species were interbred which further complicated the genetic base issue. Consequently, birds of old breeds pop up with the farmer being unaware of the kind of bird that he has produced. Some varieties that have made a comeback are Lavender Harvest Gold Auburns that originated in the 1700s, Fall Fire and Chocolates. Zane raises more Chocolates and is particularly fond of the breed because they are the only breed originating in the South. The Civil War wreaked havoc with only 12 birds surviving, though they are far more secure today. Zane is hoping to increase the size of his cherished Chocolate flock.

The entire genetic base issue is further complicated by the fact that poults are born of only a few combinations of colors regardless of species so that identification of the particular species by the color of a poult is next to impossible. For example, Fall Fire poults can be any of three colors with the Sweet Grass and Red Sweet Grass breeding true.

The importance of the Graham operation cannot be over emphasized. Zane is providing a genetic repository that hopefully others will use as part of the effort to guarantee the continued existence of these beautiful heritage birds.

I am interested in trying a breed out here in Arizona. I sent an email asking about the Belted White and Slate, but if there is a cold-intolerant breed, I would go with that instead.