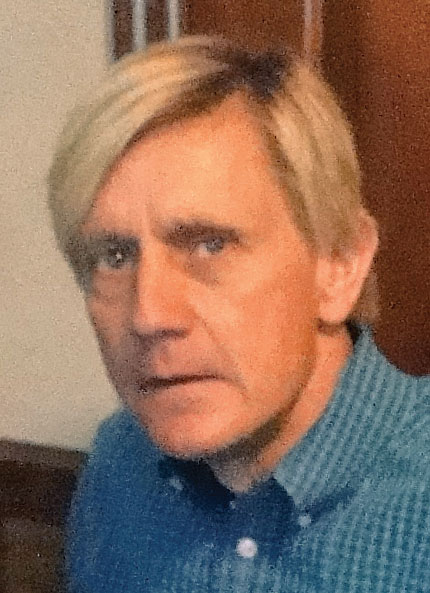

At the age of 26, Steve Harris of Fayetteville, Ark., was at the top of his game in the Quarter horse racing world, but as fate would have it, an accident nearly 30 years ago changed his life forever, but never diminished his love for horses, nor the work ethic that was instilled in him by his father and uncle.

His earliest horseback memory is being led around by his grandfather, Roy Thorton, on a Shetland pony named Strawberry at Starr Valley Angus Farms near Stilwell, Okla. It wasn’t long until a young Steve was training and selling ponies for Ponies of America, where the show ponies had to be under 12 hands tall and ridden by youngsters under the age of 12.

Steve’s father, Boyd, taught Steve that work wasn’t an option.

“If I was too lazy to get out of bed on a Saturday, my dad would throw a glass of water on me,” Steve recalled with a chuckle. “That only had to happen twice before I learned to get up as soon as I heard the water running. My dad and uncle, Floyd Harris, were poor. They worked hard and paid for their own educations. Both became dentists and taught me by example that you never say can’t or won’t.”

Steve always had chores with cattle or horses, and when he was 12, Steve had his first job at a racetrack, working in the steward’s tower by running finish photographs and bringing coffee.

By the age of 14, Steve was riding at unofficial brush tracks in Arkansas and Oklahoma; and he was in high demand because he weighed only 60 pounds and could ride. In addition to racing on Sundays, Steve also worked at Venna Lee Farms, which bred Thoroughbreds, in Fayetteville, Ark.

At 16, Steve was looking forward to a summer at home, but his father told him he needed to go work at Arlington Racetrack in Illinois. He was given a job “walking hots,” which means to cool off the horses by walking them. After the boss saw him riding a track pony one day, Steve started a new job galloping racehorses horses in the early mornings.

However, Steve’s heart was with Quarter horses. When he graduated high school, he started riding full-time at Blue Ribbon Downs in Sallisaw, Okla., and later in Ruidoso, N.M.

Steve soon demonstrated he was a talented jockey. He had the ability to communicate with still green 2-year-old racing Quarter horses with a calm assertiveness that led those horses to many victories. He raced for nine years and established an impressive winning record, including a 1983 victory at the All American Futurity on a horse named On A High. The purse was $2 million.

On May 9, 1986, Steve won six of the 10 trial heats he raced that day for the Black Gold Futurity Trials. He was dressed and ready to leave the track when the trainer of Native Judge asked him to run one more race because Steve had won on the horse previously.

The race was 870 yards, a dangerous length because the race starts on a turn. He was in the ninth position out of 10 and running to the rail when a younger jockey on the 10th position horse cut out in front of him. With another horse on his other side, Steve was blocked in. Clipping heels with another horse, Native Judge went down. Steve was thrown from the horse and suffered a broken back. He has been confined to a wheelchair ever since.

“The best advice I ever got came when I started racing in New Mexico and was asked to become a member of the Jockeys’ Guild,” Steve said. “I was young and was not about to give up any of my money for membership dues or contributions to the insurance fund. Then Jerry Nicodemus, the ‘King of Quarter Horse Racing’ back then, and Jackie Martin, an outstanding Arkansas jockey and one of my heroes, both told me I needed to join. I did, and it was one of the best decisions of my life.”

That insurance fund allowed Steve the best surgeons with a two-week hospital stay, as well as a three-month rehabilitation stay at Craig Hospital in Colorado.

Determined to take charge of his own life, Steve returned to his Fayetteville, Ark., duplex and earned an agribusiness degree at the University of Arkansas. Oddly enough, he accepted a salesman position at the Darryl Hickman Chevrolet in Siloam Springs, Ark., which later became Superior Chevrolet.

“When I got there the first day, someone made the comment that they couldn’t have a kid in a wheelchair selling cars, but I proved them wrong and am still there,” Steve said.

The work ethic that characterized Steve’s racing career remained strong and defined his career off the track as well.

“The biggest challenge was finding time for my son, Hayden, who is now 16; especially considering the long salesman hours, which included Saturdays and late nights,” Steve said.

Steve has maintained his love and interest with racing and animals, and has part interest in two racehorses and raises commercial beef cattle. Hayden takes after his father’s love of animals but in a different way.

He won a national mutton busting title and went on to ride calves and junior bulls. Last year in Las Vegas at the Indian National Finals Rodeo, Hayden took second place by a few points in the junior bulls competition.

Steve admits he is uncomfortable with the dangers of bull riding and is hoping to interest his son in raising bucking stock.

“Hayden is young, but beginning to learn the value of hard work,” Steve said. “I was reassured that at his wrestling banquet, where he received the Ed Culver Award, which is given for showing try and grit, and the ability to never give up or quit.”