A shootout with the Barrow gang in 1933 killed the newly-elected city marshall

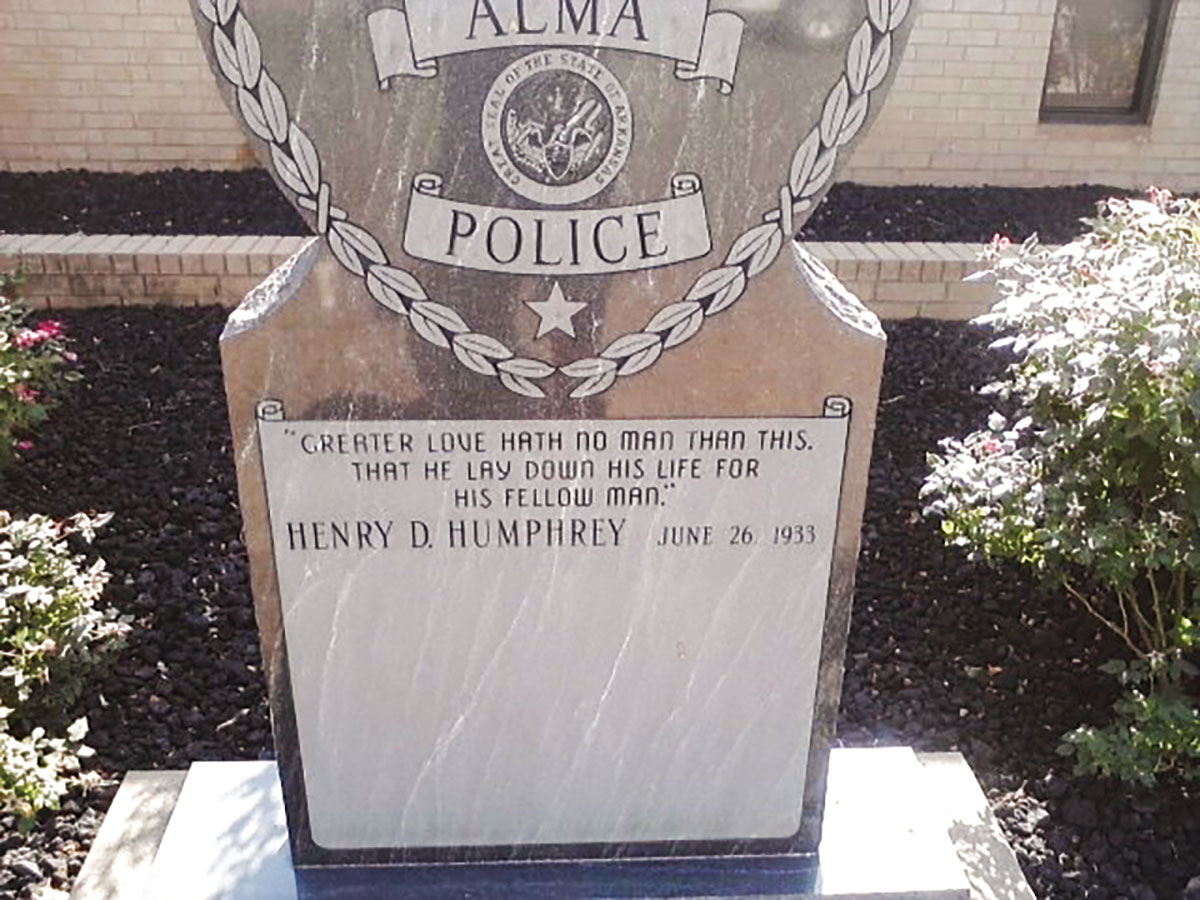

ALMA, ARK. – Just outside Alma, Ark., City Hall stands a memorial to honor law enforcement officers who have given the ultimate sacrifice to protect and serve their community. The monument, erected in 1986, has only one name memorialized — Henry D. Humphrey.

Humphrey, a farmer and handyman by trade, died on June 26, 1933, only two months after he had been elected town marshal. He died after a gunfight with an infamous gang of outlaws: The Barrow gang.

Accounts of what happened that faithful day may vary, but the outcome was the same — the 51-year-old father of three was dead.

Humphrey was on a walking patrol in the early morning hours of June 22, 1933, and was jumped by two men outside a bank in downtown Alma, which was once known as the “Spinach Capital of the World.” The men tied Humphrey’s hands with baling wire and took his pistol and flashlight. The outlaws then broke into the bank and stole the safe.

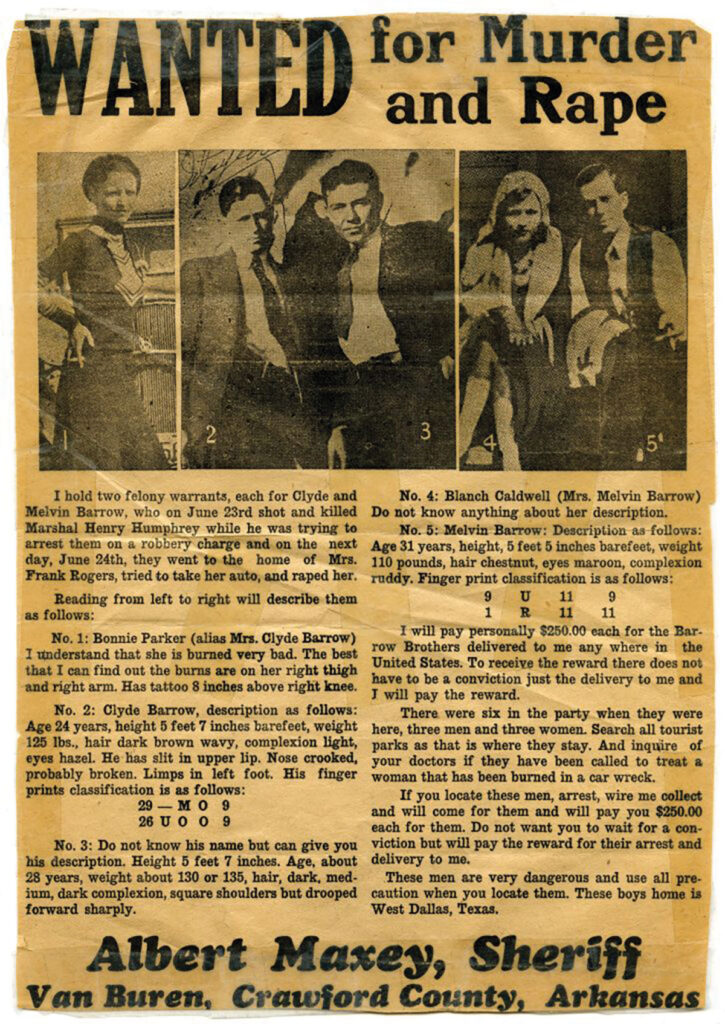

At that time, no one knew Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker and their gang were holed up at a tourist camp only minutes away in Fort Smith, Ark. They were known to frequent Arkansas, and he gang was recovering from a June 10 car crash in Wellington, Texas, that left Bonnie with extensive burns.

On June 23, 1933, published reports say Clyde Barrow told his brother Buck Barrow and gang member W.D. Jones to get some cash to hold them over while Bonnie recovered. The duo robbed a grocery store in Fayetteville, Ark., taking away $20 and change. They fled for Fort Smith, and police spread the word to be on the lookout for a Ford sedan. After hearing the getaway car was coming toward Alma, Humphrey, armed with a borrowed gun, and A.M. Salyers, a Crawford County deputy sheriff, headed out on U.S. Highway 71 in Salyers’ patrol car. On their way out of town, a Ford sedan passed them in the opposite direction and rear-ended a slower-moving car. Humphrey and Salyers heard the crash and turned back.

According to an account reported in The Arkansas Gazette, Buck Barrow and Jones were still in the wrecked car when the lawmen arrived. Humphrey didn’t have an opportunity to draw his pistol as the robbers started firing as he stepped from the car. He was hit in the stomach, chest and shoulder.

Slayers ran toward a nearby house for cover and was hit in the posterior by a bullet. Bullets passed through the house and barn, just missing a man working in a nearby field. After the gunfight, the shooters grabbed Humphrey’s gun and fled in Salyers’ car. It was later ditched, and the bandits stole a car in Fort Smith. They then headed back to the camp, avoiding roadblocks and walking across a rail bridge to hook up with the rest of the gang.

“The Crawford County version is that Clyde and the rest of the gang went to Fayetteville, leaving Bonnie at the camp,” Alma Area of Chamber of Commerce Director Beth Corey said. “The local story is that they [the slain Alma officer and the Crawford County deputy] posted a roadblock and got into a shootout with Clyde and the Barrow gang. The Barrow gang stood behind that Clyde was never with them in Washington and Crawford counties. That could be true, but also, they stood up for each other and they were going to stick up for their leader. All we know is what the Barrow gang said and what unraveled through the years.”

Reports from the day say the gang “terrorized the area” as police searched for them. They resurfaced on June 25 near Winslow, Ark., and a woman was beaten with a chain when she refused to hand over her car keys. She also accused them of rape, a charge she later recanted.

As he lay in the hospital, Humphrey identified photos of the Barrow brothers as the men who shot him. Other witnesses identified the shooters as members of the Barrow gang. Humphrey died on June 26.

Crawford County Sheriff Albert Maxey personally offered a reward, but the Barrow gang escaped into Oklahoma. Ironically, during her research of the local story, Beth discovered Maxey was her great-great-grandfather.

A month after the Alma incident, Buck Barrow was on his deathbed after a shootout in Iowa. Buck Borrow agreed with Deputy Salyers that he shot Humphrey.

There was no proof the Barrow gang had restrained Humphrey at the Alma bank, but it is widely believed they were responsible.

Because Bonnie and Clyde stuck to rural areas while on the run, they traveled many of the back roads they knew, so the infamous gang likely spent many days in the Alma area, undetected by locals.

“They went to places where they had connections, and the people they gathered along the way would help them,” Beth said. “They would go through Oklahoma, parts of Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. They made that loop over and over again. Once the U.S. Marshals and the Texas Rangers figured that out, that was the end for them.”

Beth said Bonnie was perhaps the most ruthless and vicious of the band of outlaws, officers were reliant to fire on a woman.

“They would stop shooting because of her, but that’s when they were able to get away,” Beth asserted. “They didn’t want their legacy to be the one who shot a woman.”

A year after the Alma gunfight, officers killed Bonnie and Clyde during an ambush in Louisiana, ending their rampage.

Beth would like to explore the history of Bonnie and Clyde in the Alma area more, all while paying homage to Humphrey.

“We don’t talk about what happened as much as we should,” Beth said. “Because we don’t have the spinach festival anymore, this is our biggest historical thing. I grew up in this area but never heard anything about it. I went to a luncheon and the speaker started talking about it. I told my dad about it and he pulled the poster up and said the sheriff was his great-grandpa. I have heard it talked about from a Fort Smith connection, but there is actually a bigger connection with Alma.

“I don’t want to memorialize them because they were pretty awful people, but we can honor and pay tribute to our marshal who lost his life.”