Wild Bill Hickok and Davis Tutt, Jr., make history on the Springfield, Mo., square

SPRINGFIELD, MO. – The downtown Square in Springfield, Mo., was once a much different place than it is today.

Springfield was on the frontier of the “Wild West” and one famous figure of that period etched his way into local history when a gunfight erupted on the square on July 21, 1865, leaving one man dead.

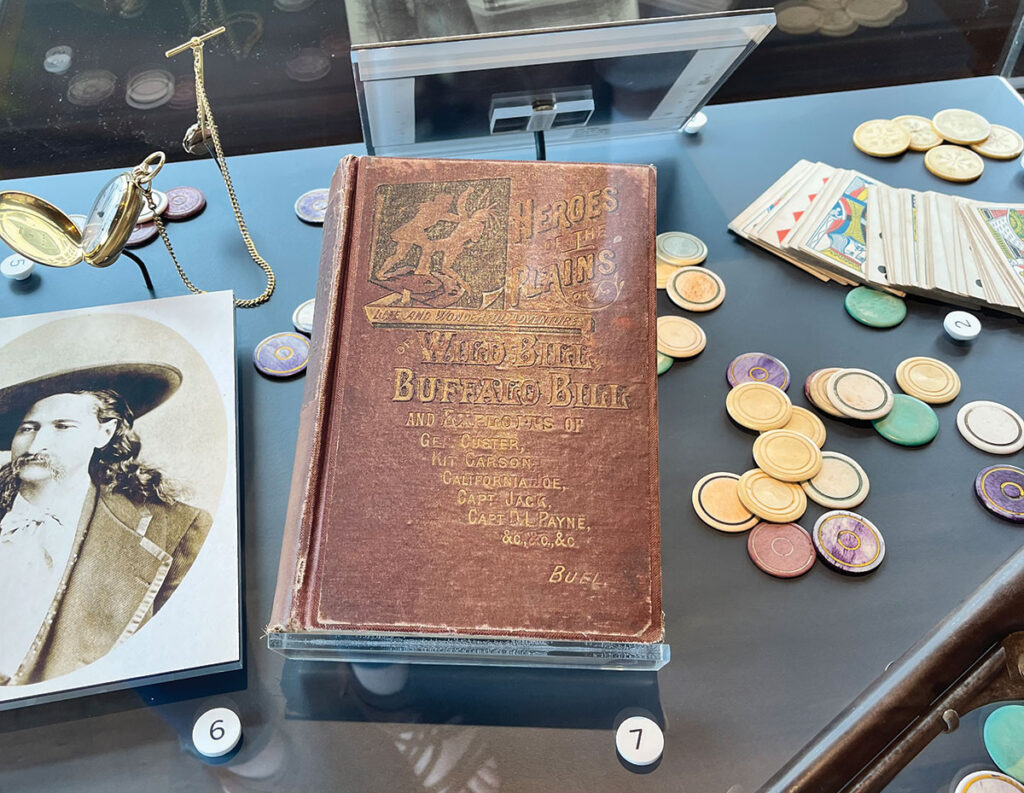

John E. Sellars, executive director emeritus, of the Springfield History Museum on the corner of Springfield’s downtown square, is a wealth of information and retells the detailed story of Bill Hickok and the shoot out. An entire floor of the downtown museum is dedicated to Hickok and shootout.

Wild Bill (as he later came to be known) was originally named James Butler Hickok, born on May 27, 1837 in La Salle Country, Ill.

His family were staunch abolitionists, who strongly believed in putting an end to slavery. Museum pictographs detail that James and his brothers assisted their father in running the Underground Railroad, allowing slaves to secure their freedom prior to the end of the Civil War.

Hickock left Illinois as a young man in search of fame and fortune. He fell into the roles of civilian scout, courier and spy. One particular assignment was a Springfield, Mo., patrol officer and militant wagon driver. He also served as a scout for Gen. Nathaniel Lyon in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.

Around the same time, Wild Bill was making his name known in Southwest Missouri, Davis Tutt, Jr., a confederate scout, made his way from Arkansas, heading north and landing in Springfield.

Both young men were active gamblers, drinkers, and known to be familiar with the female persuasion, accounting to John. They could very well be coined rowdy young men, and quickly became friends, based on their mutual interests.

While their friendship was off to an adventurous start, they encountered a falling out in July 1865. There are varying opinions as to what the disagreement was about. Some say they fought over a woman; others say there was a gambling debt Hickock owed to Tutt. The true cause of their friendship’s divide may never fully be revealed. But with drinking and carousing as mutual interests, many theories could accurately apply.

Hickock refused to gamble with Tutt based on the irreparable disagreement the two men faced. Tutt, enraged his former gambling buddy refused to engage in further business with him, attempted to retaliate by encouraging others to rack up Hickok’s gambling debts. Tutt was convinced Hickok owed him $35, which was undoubtedly worth a great deal more in 1865 than present-day currency would warrant.

At one point, the two men were seated at the same table. Hickok had removed his bulky, gold pocket watch and sat it on the table, near his person. Tutt saw an opportunity to get what he felt was rightly owed him and grabbed the expensive watch. Tutt refused to give the valuable time-keeping device back, holding it ransom as collateral and defaming Hickok to any listening ear.

Hickok was incensed his watch had been taken. He implicitly told Tutt he better not be caught wearing the expensive pocket watch, or else.

The very next day, Tutt made a public spectacle of walking across the town square, wearing the infamous pocket watch that belonged to Wild Bill.

Hickok threatened Tutt. One can only assume words were exchanged amongst both hot-tempered men, and the rest, as they say, is history.

On July 21,1865, James “Wild Bill” Hickok, and Davis Tutt, Jr., stood 75 feet apart in Springfield’s downtown square, facing each other in proper dueling fashion. Seconds later, both men drew their guns and shots were fired. Davis Tutt, Jr. missed his target. Wild Bill Hickok did not. His aim was impeccable, blasting Tutt square in the chest. One shot was all it took. As Tutt ambled, mortally wounded, toward the courthouse steps (which is where the Heer’s Building in downtown Springfield is presently located), he defeatedly said: “Boys, I’m killed.”

According to the pictographs in the museum, this dramatic scene came to be known as the first recorded shoot-out in the West.

There was a warrant issued for Hickok, but he chose to turn himself in. Wild Bill was put on trial. John S. Phelps, who later became the governor of the state of Missouri, served as his defense attorney. The judge, Pony Boyd, known for his generous founding of north Springfield, presided over the case. As the trial came to conclusion, Wild Bill was found innocent, citing self-defense as his plea and saving grace.

Tutt was buried in the Maple Park Cemetery, not far from where Missouri State University stands today. Tutt’s half-brother, Lewis Tutt, was a wealthy and prominent member of Southwest Missouri society. His family was the first African-American family to acquire a plot in the Maple Park Cemetery. Lewis allowed his brother to be buried in the family plot, but did not provide access for a headstone. Years later, the Springfield Historical Society, erected a headstone for Davis Tutt, Jr., which can be found in this historical cemetery today.

The fourth floor of the history museum houses several life-size displays and printed information about the downtown shoot-out. There is even a shooting range for children and adults to practice their aim.

Many other interesting facts about Wild Bill can be found in the museum showcase. He spent much time in Cheyenne, Wy., where he met his wife, Agnes Lake Thatcher, a well-known circus performer, known for dancing, walking the tightrope, taming lions and horse-riding. The two were married on March 5, 1876 in Cheyenne.

Just a few short months after his wedding, on a steamy summer’s day in early August, Wild Bill was playing poker in Deadwood, S.D. His back was to the door. A man named Jack McCall walked into the saloon and shot Hickok in the back of the head. He died on the spot at 39 years of age. He was holding two black aces and two black eights, which has become known as, “the dead man’s hand”.

Hickok was buried at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, where visitors can find a bronze replica of the original tombstone.