The Lady Linda Byrd Smith Museum of Biblical Archaeology was established at Harding University in 2017

SEARCY, ARK. – When most people think of archaeologists, they first think of Indiana Jones and then of digging up old bones and hunting for treasure. Little do they consider the extensive work after an object has been found.

Professor Emeritus Dr. Dale W. Manor’s first career was in ministry. He then graduated from the University of Arizona with a Ph.D., in biblical archaeology which then led to his connection with the long-term Tel Beth-Shemesh Archaeological Excavation in Israel.

In 1996, Dr. Manor came to teach at Harding University’s College of Bible & Ministry in Searcy, Ark., with the hope of further developing the university’s biblical degree, while also serving as the field director for the site in Israel. Harding’s robust degree serves as preparation for ministry and as a first step towards graduate school and possibly a Ph.D.

Part of Dr. Manor’s commitment involved providing Harding University honors biblical students with as authentic an archaeological experience as possible. He and his wife Sharon constructed a dig site duplicating real excavations sites for students to excavate according to rigorous archaeological procedures.

Even though Dr. Manor recently retired from teaching, he is still active in the university. He is the club sponsor for the archaeology club he founded in 1999, and is usually involved in an annual multi-day biblical convention held at the university, a tradition for the last 98 years. The multi-day event attracts a worldwide audience and typically focuses on a book of the Bible such as this year’s topic of the Book of Daniel with additional side topics such as church relations and belief issues. Finally, he travels five or six times a year across the nation for speaking engagements.

For many years, Dr. Manor’s small office was overflowing with books and papers, in addition to housing numerous artifacts and reproductions. He wanted to share his collection with others by creating a museum. Although funding was a difficult problem, the solution evolved from a friendship.

Through traveling occasionally to the Holy Land with Old Testament expert Dr. Jack Lewis, a Harding alumnus named Linda Byrd Smith became friends with Dr. Manor. Now and then he lent her pieces to use in seminars. A 200-year-old Bedouin wineskin made from goatskin may have been the first. The two enthusiasts bonded, and Dr. Manor occasionally obtained items from Israel for her in addition to sometimes calling while traveling there to see if she wanted anything.

Because of her deep interest and commitment to the archaeology of the biblical world, Linda offered to finance the necessary room renovation for Dr. Manor’s museum. In appreciation, the museum was named the Lady Linda Byrd Smith Museum of Biblical Archaeology.

The museum, founded in 2017, contains both a permanent collection and a temporary one rotated out every two years. Museum artifacts demonstrate extensive trade during those early years with objects found in Israel coming from lands as distant as Cyprus, Greece and Egypt. The next temporary collection is in current development and will emphasize Egyptian artifacts and reproductions. Expected to be included are Egyptian tool reproductions which are anticipated to feature a replica mallet made of acacia wood as mentioned in the Bible and a reproduction of a bow drill that would have been used to drill holes in stone and wood for everyday and ceremonial objects. On some artifacts, such drilled indentations were filled with fragrant oils such as the incense frankincense and the embalming oil myrrh, two of the three gifts from the wise men to Jesus.

“The Biblical narrative is rooted in historical events,” Dr. Manor explained. “I am not using archaeology to prove the Bible but to help others better understand the lives and cultures of those people. My goal is for students and visitors to realize the ancients were little different from the way we are today.”

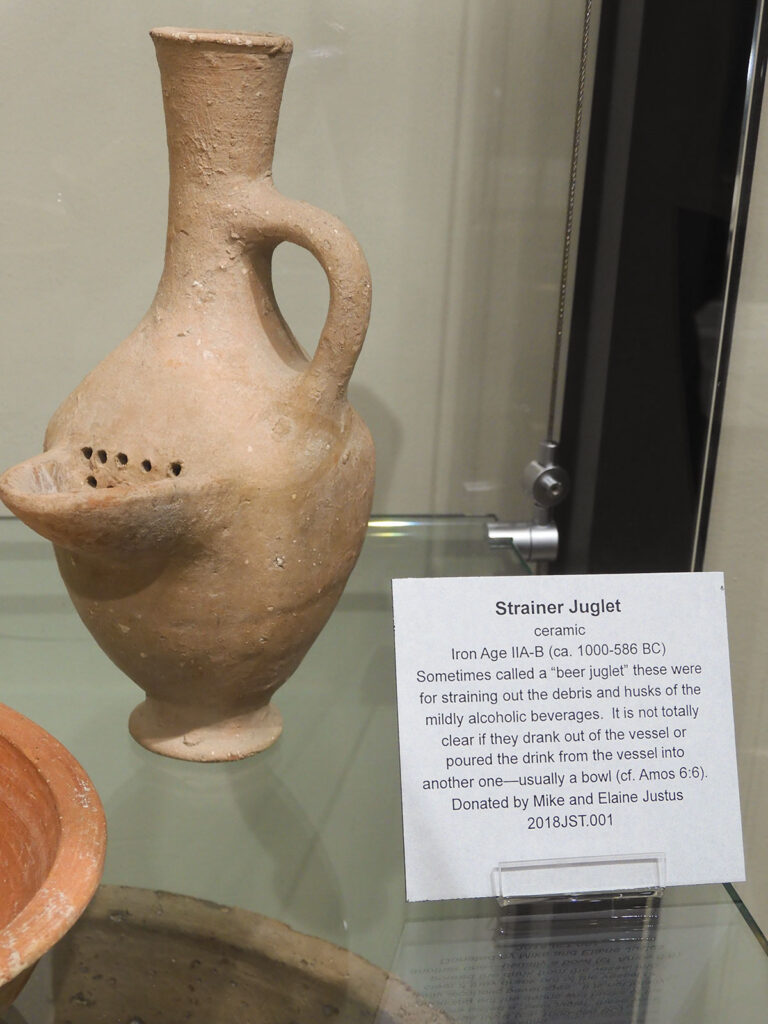

Dr. Manor’s clear vision of his role as an archaeologist brings to mind the old adage that the more things change the more they stay the same. Several museum artifacts stand out as examples of both the resourcefulness and intelligence of people during biblical times. One is a pottery wine vessel with four holes drilled in the upper part of the sides. These holes were sealed with hollow pottery tubes to prevent leakage but which permitted water in a stream to flow through the tubes, thus cooling the jar’s contents. Just like us, the ancients liked chilled wine and submerged the vessel in a stream or river which allowed the cold water to chill from the top and bottom.

Another resourceful artifact is a container for olive oil with a pitcher-like handle “decorated” with a small hollowed disc on top. That depression contains a hole leading to the inside of the container. The purpose of the depression was to hold a small dipping cup for access to the oil. Then the used cup would be placed in the depression so that the oil on the outside of the cup would drip back into the container. Conservation was as important then as it is now.

Two examples of ancient intelligence are the development of a square with a plumb bob little different from today’s squares and critical for the building of the pyramids. Additionally, they used scales which served as a critical element of ancient commerce. Through the thousands of years, their basic design and uses have changed little.

While ancients honoring the dead, especially the wealthy, is not surprising, one of their habits is. A prized museum possessions is an ossuary, a stone box the size of a small chest that served as a type of coffin. It housed the skull and long bones of the deceased with hip bones preserved elsewhere. Body preparation was very similar to the way Jesus was prepared for burial. A body was laid to rest on a raised stone slab and then perfumed and sprinkled with spices to compensate for the smell of decay. Next it was wrapped in linen. Then, about a year later, the linen was removed and the bones placed in an ossuary. A single box could contain bones from as many as six people. The boxes were typically stored in hand-carved caves with tunnels leading deeper into the hill or mountain. These typically belonged to a wealthy, multi-generational family. However, the ancients were not above littering. Empty perfume bottles were carelessly discarded in the preparation area which accounts for the large numbers of perfume bottle artifacts from ancient times.

While crucifixion is a well documented ancient execution process, only two pieces of physical evidence have been discovered so far that preserve actual evidence of crucifixions have been discovered so far. The first was discovered in Israel in 1968 in a huge 2,000-year-old Jewish cemetery over. The artifact was examined by Jerusalem’s Hebrew University Medical School and determined to be a heel bone pierced by large nail with a hooked end. The second artifact was recently discovered in Italy in 2018 and was also part of a foot. Harding’s museum contains a replica of the first carefully displayed next to an actual ossuary. The replica is placed next to a piece of timber topped with a crown of thorns. Adjacent is a carefully produced skeletal foot demonstrating what the entire foot would’ve looked like. The display is chilling and compelling.