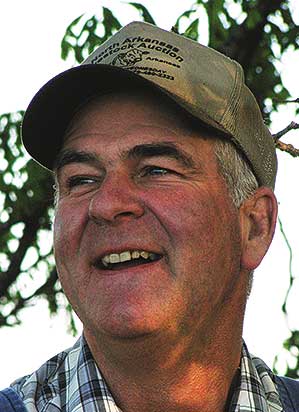

Reed Haynes is a third generation farmer in the Charleston, Ark., area. His grandparents started their farm, and then passed it down to their son Herman Haynes, Reed’s father.

“Dad was a historian,” Reed smiled. He remembered being told that his father’s grandfather, John Haynes, bought a slave after the Civil War, and later the family gave this man his freedom, and the Haynes family name. They let this man live on their place, and hired him on to help with the farm.

“My family still has the receipt today,” a handwritten note guaranteeing the sale of the man, Reed said, thoughtfully.

Time has brought changes for the Haynes family, indeed. Reed’s father, Herman, was farming in the mid 40s when Fort Chaffee officials came in and ordered him off of his land. When they did this, his father didn’t have enough land to farm full-time, so he sold 104 acres of the farm and moved to Charleston. In 1946, however, he saved part of the old farm, some of the original land that the government gave the family to homestead.

Reed’s father owned two or three grocery stores in town, and growing up Reed helped in the stores. He also helped hid dad with the cattle.

When he got married – to Barbara, who he’s now been with 53 years – Reed went to work for the sheriff’s office. He would go out and feed for his dad on the side still, because his father would get off work well after dark most of the time. His father gave him some cows during this time. In 1976 Reed and Barbara rented her family’s farm after they moved into town. They still have that place today.

Reed started with 25 heifers. “I kept thinking, if I add 50 more, I will make more money,” he smiled.

When Reed reached 150 head he realized you make about the same whether it’s 25 or 150. Reed started with Hereford cattle and then went to commercial cattle. He started buying Black Angus bulls and putting them on his Hereford heifers, to get the Black Baldys and more black cattle. “That is the preference in today’s market,” said Reed.

“My grandfather handed down the farming to my dad, and my father handed it down to me. I was taught so much about farming by my father, and I, in turn, have taught my sons the same way. And I hope my grandsons will also choose the farming way of life,” said Reed. Reed’s sons are Wally and Mike.

“If you manage well, you can do well,” said Reed, “I always said if you are not making money in your sleep nowadays, you can’t make it, and in order to do that you need to have a cow and a calf growing in a pasture somewhere.”

“We rotate pastures according to the grass, we cross fence part of the pastures and kind of let the cows tell us when it’s time to move, we spray and brush hog the pastures often, and watch the grass. Good management of the pastures is a key to good productivity,” said Reed.

“We start calving early, by October we are through and then in December we put the bulls back in. I like for the cows to rest for about three months before we put the bulls back in with them.”

Retirement is now in the future for Reed.

“I am a member of the Cattleman’s Association in Franklin County, Arkansas, and I plan on recruiting for them when I leave office,” he said.

“I would not change one part of my life as a farmer, or as a sheriff. I have served my community to the best of my ability and at 72 years old, I think it’s time that I return to the farm and my family.”